DOE Study: AI Boom Breeds Localized Energy Constraints, But Grid Can Meet Long-Term Demand

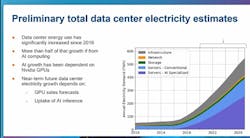

WASHINGTON, DC - Data center energy use in the United States has doubled over the past three years and is expected to grow by another 50 percent by 2027, according to preliminary results of a new government study.

The 2024 Report to Congress on U.S. Data Center Energy Use is designed to assess how surging interest in artificial intelligence (AI) is impacting the technology industry’s use of electricity. Demand for AI will likely alter the geography of digital infrastructure, but isn’t going to gobble up all the power on the electric grid, say government researchers from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), part of the Department of Energy.

“We’re driving towards electrification, so an increase in electricity use by data centers is expected,” said Arman Shehabi, staff scientist at LBNL, who noted that there is also growing demand to support electric vehicles and residential heat pumps and appliances. “It’s going to happen first with data centers, so the data center industry has an opportunity to lead in how this growth in demand is addressed strategically.”

Data center electricity use currently stands at about 375 terawatt hours (TWh), up from about 175 TWh in 2021, said Shehabi, who shared a preview of the report Thursday at the Data Center World conference.

The power requirements for AI hardware are likely to push data center energy use past 500 TWh by 2027, Shehabi added, cautioning that rapid shifts in AI hardware and adoption make forward projections difficult.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty in there,” he said. “Is there going to be that much growth? We don’t know that yet.”

Power Constraints Alter Data Center Geography

It’s becoming clear that the data center industry will likely struggle to find adequate power in some locations, as transmission constraints force data center construction into new markets, according to multiple experts who spoke at Data Center World.

The surging demand for AI compute from giant tech companies will also require closer collaboration between data center developers, utilities and grid operators.

Power constraints are already being seen in Northern Virginia and Atlanta, as well as parts of the Suburban Chicago and Dallas markets – four of the largest markets for digital infrastructure. There are also early signs of constraints in fast-growing hyperscale cloud clusters in Central Ohio, Montreal and Hillsboro, Oregon.

Meanwhile, demand for new construction is off the charts. Projections shared by analysts at Data Center World ranged from 22 gigawatts (GWs) to 35 GWs of data center construction in the pipeline.

That disconnect is forcing new thinking on data center site selection.

“We used to say ‘bring the power to the data centers,” said Ed Socia, Insight Director for North America at datacenterHawk, a research firm that tracks data center activity. “Now we say ‘bring the data center to the power.’”

Socia says developments are shifting to markets with power availability like Charlotte, Austin, San Antonio and Reno.

Ali Fenn, the President of data center developer Lancium, sees opportunity in building data centers near renewable energy sources, especially the wind and power generation in parts of Texas.

“Texas is a very, very hot spot for data center operators as they think about how to deploy new capacity,” said Fenn.

In coming years, data center developments could track the development of small modular nuclear reactors (SMR), said Colby Cox, Managing Director - Americas for analyst firm DC Byte. Cox noted that there are 37 different SMR projects proposed in states with little or no data center footprint.

Grid Constraints Are Localized, Time-Sensitive

The need for new site selection strategies was affirmed by the team at LBNL.

“There could be challenges meeting demand in certain locations, within a certain period of time,” said Shehabi. “But we think that there will be other locations where that power could be addressed or met.”

Sarah Smith, a Research Scientist in LBNL’s Sustainable Energy group, noted that there are 3,000 gigawatts of renewable energy generation in development across the U.S., but that capacity is delayed by interconnection queues at grid operators.

“That queue has become bloated, and it takes time to work on that,” said Smith. “There’s a timing issue. If you want it right now, that’s different question than whether power will be available in the next 5 to 10 years. It’s a more localized issue, where certain grids aren’t able to build that (demand) out."

Shehabi said that recent headlines suggesting that AI demand could threaten electricity supply on a national or global scale appear to overstate the risk.

“Most of those studies are taking the higher numbers that you’ve seen claimed (for future GPU deployments) and taking the maximum amount of power that those GPUs could run, and multiplying that together and extrapolating them out,” he said. “Those are two things that are not understood very well. That’s the high-end value of what we’ve seen."

“The amount of generation capacity online is so large, on a national scale, that we don’t see an issue with the growth of data centers,” said Shehabi. “The challenge comes if you want the electricity in a certain location at the certain time. The problem is localized.”

A Second Revolution in Data Center Energy?

Shehabi also noted the data center industry’s history of innovation and track record in addressing energy challenges. The U.S. government began studying data centers after their energy usage soared between 2000 and 2010. But that trend did not continue.

“Between 2010 and 2018, data center energy growth was flat at about 6%, while compute use rose 550%,” said Shehabi. “The entire industry grew fantastically, at the same time that it was able to counteract that with efficiency, allowing the electrical use to stay pretty flat. “

The huge efficiency gains were brought by the rise of cloud computing and hyperscale facility designs that optimized for energy use at massive scale. Similar innovation by tech titans is likely to be applied to AI-related energy challenges.

“What will be the big technology shift in the 20s? We’re not sure yet,” said Shehabi. “But there’s a lot of opportunity here for how that demand can be met. A lot of opportunities of working with the utilities have been discussed and are being worked on now.”